We kindly inform you that, as long as the subject affiliation of our 300.000+ articles is in progress, you might get unsufficient or no results on your third level or second level search. In this case, please broaden your search criteria.

Jeff Stickney: Tell us when and how your productive collaboration began. Who else played a part in ushering in a new, post-foundational reading of Wittgenstein within philosophy of education? Michael Peters: First let me express my gratitude to you both but particularly Jeff for organizing this interview. As far as I remember our collaborations began with contributing to Jim Marshall and Paul Smeyers’ Wittgenstein’s Challenge published in 1995. We were contributors to the same collection.

More...

I have known Michael Peters for more than 30 years. My first encounter with him was in the 1970s at an Auckland secondary school where I was a student and Michael was a teacher. I was not in Michael’s classes but did see him in action once or twice when he appeared in a Social Studies course taught by someone else. Those memories are hazy now but I have a clear recollection of our subsequent crossing of paths at the University of Auckland in the early 1980s. In my second year at university I enrolled in two Stage One Education courses, one of which was titled ‘An Introduction to Western Educational Thought’. Colin Lankshear and Jim Marshall were the course lecturers and Michael was my tutor. Michael was completing his PhD at the time (with Jim as his senior supervisor), and he was an enthusiastic, thought provoking tutor. He probed us to think more carefully and deeply in responding to educational questions and he played an important role, with Colin and Jim, in fostering my interest in philosophy of education. He was also willing to meet outside class times to discuss essays and other aspects of the course, for which I was most grateful. I went on to major in Education for my BA degree and Michael was involved in a number of the other courses I completed. A Masters degree in Education followed, and in 1987 I was interviewed for a Junior Lectureship at the University of Waikato, an institution located about two hours south of Auckland. I was offered the job and thereafter my contact with Michael lessened for a number of years, though we did see each other at conferences and other events from time to time.

More...

In his indefatigable endeavours, Michael Peters has opened a large and complex terrain. Conceptually, it offers an horizon against which large ideas have been explored, including those of globalization, postmodernism, postpostmodernism, governmentality, ‘knowledge capitalism’ (Peters’ own term), neoliberalism, education, pedagogy, social policy, economic policy, knowledge, culture and openness. Key theorists and thinkers on whom Peters has drawn have included Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault, Lyotard, Readings, Derrida, Rorty, and Deleuze. An oeuvre with such scope lends itself to an almost infinite interrogations, and interpretations, even when placed in the themes of this volume – those of education, politics and the cosmopolitan. In this chapter, I shall home in on just one matter, that of understanding the university: just what is it to understand the university? And I shall try to address this question in the spirit – as I glean it – of the breadth of perspectives bequeathed to us by Michael Peters.

More...

It may strike the genteel reader as odd that a revolutionary Marxist humanist educator is penning the endword to a volume dedicated to the storied postmodernist/poststructuralist philosopher from Aotearoa, the land of the long white cloud. And whilst some might view ending a book about the person and work of Mike Peters with a Postface by an author whose own work has been largely and on occasion virulently inhospitable to post-structuralism over the past several decades as a risky preemptory wager, it wouldn’t seem odd to Mike Peters. He would no doubt be pleased if I were to instantiate an ambiguous Marxist co-presence into a volume celebrating his work, not because he has any particular affinity with the well-trodden path and contradictory history of Marxism, but because of his indefatigable commitment to including diverse systems of intelligibility in examining the nature of our contentious present with its seemingly intractable social and political disjunctions. Mike is a warrior for diversity, it’s part of his ontological clarity and is what makes him such a commanding intellectual and a man of both the future and present. Mike writes in a white heat, spinning his ideas into the eschatological future where is he able to announce a state of affairs that both is and is to come.

More...

Peter McLaren wrote this piece last and so I come to it last and have recast it as an endword rather than a foreword because I think this will become the basis for an ongoing dialogue of which this exchange is only the first stage. It is so different from the other articles that I decided to engage with it as a postscript or endnote. Peter is a great friend. He is a “mate” as we say in New Zealand and I regard him as a brother and it is with affection that I engage with his ideas here. Where a number of the other contributors attempted to define me in their terms—I am a secret Kantian, universalist or cosmopolitan even if I don’t already know it—Peter seeks to define me by what I’m not and especially by contrast to what he is—a revolutionary Marxist. And he takes up the cudgels on behalf of revolutionary Marxism against postmodernism and poststructuralism which are movements that allegedly define me. This is a tricky assignment for Peter as a revolutionary Marxist because he is on record as being against both postmodernism and poststructuralism and yet at the same time he is my friend and wants to be able to be respectful and to say some nice things. He manages to achieve this very well and with eloquence. I am both flattered and relieved frankly— that we can remain good friends. But I like him and treat him as a brother (even though I have qualms about “brotherhoods”) not because he is a revolutionary Marxist but despite it. He could have been a Mormon.

More...

This chapter will consider the significance of public deliberation for decision-making on bioethical issues. In the past couple of decades, deliberative democracy has become the dominant point of view in democratic theory. There is no doubt that bioethics is the field marked by numerous reasonable disagreements. However, some authors have expressed a view that it is precisely because of this that deliberative democracy can be of immense importance in this context. In this chapter, I will primarily discuss the role of public deliberation on human biomedical enhancements. This is the reason why I will discuss the view of Alan Buchanan, who maintains that in order to face problems associated with biomedical enhancements, it is crucially important that there be an appropriate institutional framework.

More...

The technique to solve real problems is offered. The technique consists of five steps:1) recording of the conditions of problem; 2) statement of aim of the problem; 3) identification of the causes of appearance problem; 4) finding ways of solving the problem; 5) analysis of the solutions. The essence and content of each stage is discussed.

More...

This paper is devoted to the publication and analysis of the letters written by N. E. Makarenko to A. M. Talgren in the period from March 1917 till September 1935. The letters are kept in the Manuscript Department of the Finland National Library. The correspondence is divided in three periods: Petrograd period (March—April 1917), Kiev period (October 1925 — March 1934) and Kazan period (September 1935). The subject of the correspondence were publications in the journal “Eurasia Septentrionalis Antiqua”, excavations of the Mariupol burial mound, Makarenko’s efforts to organize the archeological research in Kiev etc. The dramatic events in Makarenko’s private life, such as exile, detention and execution on 4 January 1938 were also reflected in this correspondence. The letters are supplied with comments and notes.

More...

Ad memoriam M. B. Shchukin

More...

The doctrine of the ‘separation of spheres’, prevalent in 19th century Victorian England, attributed to women the roles of obeying daughters, submissive wives and dutiful mothers. Such roles were to be played within the narrow confines of the house, symbolized by the domestic, private sphere. The ideal woman, the ‘angel in the house’, was seen as a pure, pious, weak, dependent, fragile, self-sacrificing wife and mother. She was bestowed the major role in raising the children and taking care of the house. Men, the bread-winners, belonged to the social or public sphere and were seen as active, independent, strong and dominant.The Portrait of a Lady, belonging to James’ early period of creation and regarded as one of his best novels, introduces a wide gallery of feminine and masculine characters: sisters and brothers, wives and husbands, mothers and fathers. Thus, Isabel Archer, Madame Merle, Lydia Touchett, Mrs. Osmond and Amy Gemini, apart from other roles played in the novel, appear, to a greater or lesser extent as mothers in James’ text. On the other hand, Daniel Tracy Touchett, Gilbert Osmond and Isabel’s father are attributed the role of paternal figures.To what extent do these characters comply with the parental roles attributed by the patriarchal 19th century Victorian society? How motherly are the mothers and how fatherly are the fathers that populate James’ novel? The paper analyses the characters in The Portrait of a Lady in terms of their conformity to and/or departure from the mother and father roles prescribed by the society of the time.

More...

The book, an example of breaking literary conventions, comprises the texts concerning different, often absurd, aspects of reality. It is a critical analysis of academic work, which compels self-reflection and warns against perceiving the world in a stereotypical way and a wordplay, which oversteps the boundaries between the language and imagination.

More...

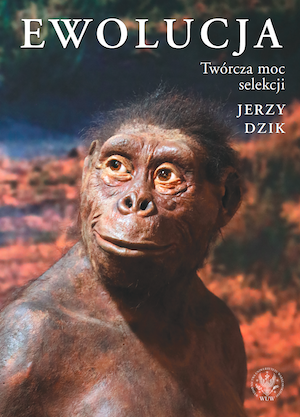

An instructive introduction to the theory of evolution and its applications in biology, physics, chemistry, geology and humanities. The author shows that evolution is a physical process, occurring in geological time dimension, describes how the Darwin’s theory of natural selection works in immunology, neurobiology, sociology as well as in certain aspects of culture and political institutions. He also shows the effects achieved through the action of selection in different areas of biological and social life. He discusses such problems as: the ambiguity of the term “theory of evolution”, the falsifiability of evolutionary hypotheses, connection between evolution and thermodynamics, the concept of reductionism, methodological background of phylogenetics, cladistics, evolutionary developmental biology and homeotic genes, as well as the cumulative nature of social and cultural evolution.

More...

Institut za društvena istraživanja je organizaciona jedinica Fakulteta političkih nauka u Sarajevu, člana Univerziteta u Sarajevu. Institut podržava naučnoistraživački rad kao ključni faktor za razvoj nauke i obrazovanja, za shvatanja društveno-političkih procesa u Bosni i Hercegovini i okruženju, te za stvaranje društva utemeljenog na znanju. [...]

More...